Welcome!

Welcome! If you are starting off on this page, let’s help you get yourself oriented. Below you will find several sections of information pertaining to common questions. If you already know what you wish to know more about, please just click one of the links below to go to that section. If you’re really new and just want to learn quickly, start in Section 1. In the Anatomy section you will find several diagrams and explanations outlining the different parts of the larval, pupal, and adult forms of these insects. The Glossary section is quite useful if you need to know what a term means.

1. Is it a sphingid?

There are a few ways to tell if the caterpillar/moth/pupa you’re looking at is in this family of moths. We can break this down into sections:

Moth: You are looking at an adult moth of some sort, neat! If you are unsure if the moth you are looking at belong in the family Sphingidae, take a look at the size. Is it really small (<4mm)? Then it’s probably not in this family. The next step is to look at the forewings, if they’re rather elongate and pointed (think jet plane shape), it’s probably a Sphingidae, especially if the moth is relatively large (>30mm)! Generally the Sphingidae have a fairly noticeable proboscis, but this is also absent in some species. Some subfamilies of these moths will sit with their forewings tucked close to their bodies, whereas some subfamilies pull their hindwings above their forewings. A good way to think about this family of moths is by examining their common names: Sphinx Moths, Hawk Moths, Hummingbird Moths. These common names, while not necessarily useful in scientific communication, are good qualifiers for these moths. They are generally large, capable of strong directed flight, and often hover over flowers for nectar (like a hummingbird). Using a variety of these factors, you can usually tell adult Sphingidae apart from other moths very easily. Checkout the Sphingidae Index for some examples.

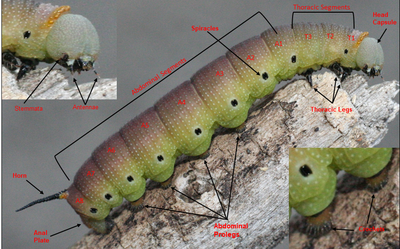

Caterpillar: The Caterpillars of this family of moths are usually very distinctive. Often quite large with a prominent horn on their rear. Not all the species have this horn, and in some it may be pretty reduced. But if it has a horn on its rear, and it’s relatively large, it’s almost certainly a sphingid. Caterpillars in this family also tend to be longer than they are chubby. Saturniidae, the other family of large caterpillars is often a lot chubbier than long, which is a good separating characteristic. Most of the other caterpillars you will find won’t be nearly large as ones in this family, and the smaller ones will almost always have horns.

Final Instar Caterpillar: Huh? Why is this separated out from above?! Well, in order to use the Final Instar Larva Key you must have found a final instar caterpillar. A final instar, or fully grown, caterpillar is just that, fully grown. They’re usually quite big, sometimes looking like they’re going to burst from eating so much, and are most frequently seen wandering around looking for a place to pupate. If you found a really big sphingid larva on a plant, it may also be final instar. Generally if it has no horn or a reduced horn, it is a final instar. If your larva has a horn and is quite big, then it may also be a final instar. It’s really hard to quantify “big”, as each species of sphingid is a bit different, but you will know “big” when you see it. I’ve heard final instar Sphingidae described as “sausages” on more than one occasion.

Pupa: This is a lot harder. Pupae are variable. If you found it above ground and wrapped in a silken cocoon, it’s not in this family. Sphingidae pupate underground and usually in a bare pupa. There are a few rare exceptions to that rule. If you’re digging (particularly in your garden) and find a relatively large pupa with a noticeable proboscis, you may have found a sphingid pupa!

Using the above descriptions you should be able to figure out if you have a sphingid or not. Once you think you do, you can proceed to the Sphingidae Index page to try and identify what you found. If it’s a caterpillar, and it’s final instar, you can use the Final Instar Larva Key.

BACK TO TOP

Moth: You are looking at an adult moth of some sort, neat! If you are unsure if the moth you are looking at belong in the family Sphingidae, take a look at the size. Is it really small (<4mm)? Then it’s probably not in this family. The next step is to look at the forewings, if they’re rather elongate and pointed (think jet plane shape), it’s probably a Sphingidae, especially if the moth is relatively large (>30mm)! Generally the Sphingidae have a fairly noticeable proboscis, but this is also absent in some species. Some subfamilies of these moths will sit with their forewings tucked close to their bodies, whereas some subfamilies pull their hindwings above their forewings. A good way to think about this family of moths is by examining their common names: Sphinx Moths, Hawk Moths, Hummingbird Moths. These common names, while not necessarily useful in scientific communication, are good qualifiers for these moths. They are generally large, capable of strong directed flight, and often hover over flowers for nectar (like a hummingbird). Using a variety of these factors, you can usually tell adult Sphingidae apart from other moths very easily. Checkout the Sphingidae Index for some examples.

Caterpillar: The Caterpillars of this family of moths are usually very distinctive. Often quite large with a prominent horn on their rear. Not all the species have this horn, and in some it may be pretty reduced. But if it has a horn on its rear, and it’s relatively large, it’s almost certainly a sphingid. Caterpillars in this family also tend to be longer than they are chubby. Saturniidae, the other family of large caterpillars is often a lot chubbier than long, which is a good separating characteristic. Most of the other caterpillars you will find won’t be nearly large as ones in this family, and the smaller ones will almost always have horns.

Final Instar Caterpillar: Huh? Why is this separated out from above?! Well, in order to use the Final Instar Larva Key you must have found a final instar caterpillar. A final instar, or fully grown, caterpillar is just that, fully grown. They’re usually quite big, sometimes looking like they’re going to burst from eating so much, and are most frequently seen wandering around looking for a place to pupate. If you found a really big sphingid larva on a plant, it may also be final instar. Generally if it has no horn or a reduced horn, it is a final instar. If your larva has a horn and is quite big, then it may also be a final instar. It’s really hard to quantify “big”, as each species of sphingid is a bit different, but you will know “big” when you see it. I’ve heard final instar Sphingidae described as “sausages” on more than one occasion.

Pupa: This is a lot harder. Pupae are variable. If you found it above ground and wrapped in a silken cocoon, it’s not in this family. Sphingidae pupate underground and usually in a bare pupa. There are a few rare exceptions to that rule. If you’re digging (particularly in your garden) and find a relatively large pupa with a noticeable proboscis, you may have found a sphingid pupa!

Using the above descriptions you should be able to figure out if you have a sphingid or not. Once you think you do, you can proceed to the Sphingidae Index page to try and identify what you found. If it’s a caterpillar, and it’s final instar, you can use the Final Instar Larva Key.

BACK TO TOP

2. Life Cycle

The life cycle of the Sphingidae is the same as other Lepidoptera. That is to say, they have an egg stage, a larval stage (with 5 instars), a pupal stage, and an imago (adult) stage. To get a bit more specific, the adult sphingids are usually very active. They fly around and many feed on nectar and live a fairly substantial length of time (1-2 weeks average). Once they mate, the females lay eggs on the hostplant desired for their species. They can sense what plant using chemical receptors on their feet. Once the eggs (usually green in color and quite circular) are laid, they take anywhere from 4-10 days to hatch. Once the first instar larvae hatch, they begin feeding. The larvae are usually very small and have a horn on their rear (some species lack this). As the larvae eat and grow, they molt into additional instars. Once they reach their fifth and final instar, the larva usually looks a lot different. It is usually large, may be quite colorful, and may have a very large horn, no horn at all, or a small nub of a horn. Once the larva is fully grown and done feeding, they leave the plant they are on. They wander for a period of time, looking for the perfect spot to pupate. Once they find it, the larvae dig down and make a chamber to pupate in. The larva pupates as a bare pupa in this underground cell. The pupa eventually wiggles to the surface, and the adult moth ecloses. The moth climbs up, expands its wings, and flies off in search of a mate. The images below are the entire lifecycle of Manduca sexta.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP

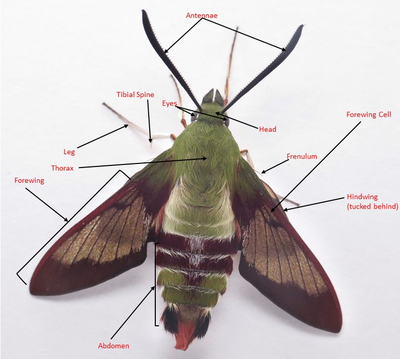

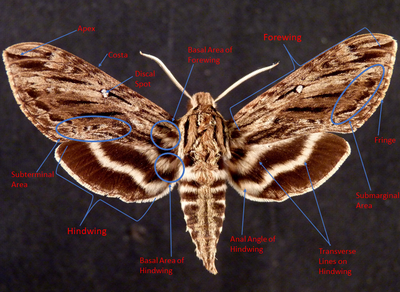

3. Anatomy

The gallery below contains images that are the general anatomy of Sphingidae adults and larvae. There is also a Sphingidae wing anatomy page for some of the technical wing terms used throughout the site. These diagrams may help you as you examine keys and species descriptions found across this site.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP

4. Glossary

- A1/T1 - A1 is Abdominal Segment 1 (or whatever number follows), T1 is Thoracic Segment 1 (or whatever number follows)

- Abdomen (Abdominal) - The posterior segment of an insect. Abdominal is used when referencing this area.

- Anal Horn - The horn found on the last abdominal segment in most larva in the family Sphingidae.

- Anal Plate - The plate right above the anal prolegs.

- Anal Prolegs - The last set of prolegs on the larva.

- Apex - The apex is the tip of the forewing

- Basal Area - The area of the wing of the moth closest to the thorax.

- Discal Spot - The spot found in the middle of the forewings of many adult moths.

- Forewing Cell - The only cell on the forewing totally surrounded by veins.

- Frenulum - The small structure found between the forewings and hindwings that join them together.

- Granulose - Grainy, distinctly so. Almost as if covered in small grains of sand.

- Imago - The adult form of an insect.

- Instar - The period of time between an insects molt. Example: a caterpillar that hatches from an egg is instar 1 (L1); once it sheds, it molts into instar 2 (L2).

- Proboscis - The tongue

- Prolegs - The sticky back legs of a larva, there are usually 4 pairs of these legs.

- Subterminal Area - The area on the lower edge of the forewing leading toward the edge of the wing.

- Thorax (Thoracic) -The area directly behind an insects head, but before the abdomen. Thoracic is used when referencing this area.

- Thoracic Legs (True Legs) - The “real” legs of a larva, often hard in appearance, found right behind the head. There are only 3 pairs of these legs.

BACK TO TOP

5. General Rearing Notes

Intro

The first topic covered in this document is how to obtain Sphingidae to rear. This can be accomplished in a few ways. The easiest is to find an adult female and obtain eggs from it. This is discussed in detail in the last section, however it is worth mentioning here too. Adult Sphingidae can be placed into a styrofoam cooler, or into a paper bag to obtain eggs. While this works for many species (particularly ones that do not feed), some species do need a flight cage with hostplant to lay eggs. Specific methods of obtaining ovae from each species can be found on that species’ page. The next way to find Sphingidae to rear is by locating caterpillars. Searching plants at night, in mid-late summer is quite productive. Many species fluoresce with a UV flashlight, making it even easier to locate them. Once you have caterpillars, you can rear them using the methods below. This document is extremely general, specific information for each species and how to rear and breed them can be found on that specific species’ page. While not every species has this information yet, we are working on updating all of them. If you have questions, please contact us using the contact form, or email us at [email protected]. Have some additional rearing methods, notes, tips, or tricks? Shoot us an email! We will update this document and other areas on the site with new information, and we always credit those who supply us with it.

Rearing Sphingidae Larvae

In this section we discuss three methods of rearing Sphingidae larvae. The first method is rearing larvae in tupperware containers. This method is incredibly simple and involves placing the larva(e) and hostplant into a large enough container to rear them to pupation. Good containers should be sealed, but not totally airtight. If the container is completely sealed, adding a few ventilation holes to the lid or side is recommended. Cut hostplant material can be placed in the tupperware with the larva. The hostplant usually stays fairly fresh in the containers, though checking is required. Every day the containers should be vented, and excess moisture wiped down. Hostplant should be changed out daily, when the larva runs out of food, or when the plant is wilted or dry. For many species, it is imperative that frass is wiped out daily as it will mold and potentially kill the larva. When done properly, this is an extremely successful method. The next method discussed is sleeving. This method is much simpler, though attention is required for full-grown larvae. To sleeve larvae, simply obtain some light-weight mesh material that allows water to pass through, Tulle is a good option. BioQuip and other Entomological suppliers will often sell premade bags that can be used. Once you have obtained material, you should make a bag that is large enough to go over a branch (or several). It is important that the bag is totally sealed so that no larvae can escape. To sleeve a larva, simply place the larva in the bottom of the bag, and place the bag and larva over a branch of hostplant. The bag should then be carefully affixed to the branch in such a manner that no predators can get in, and the larva can’t escape. This can be accomplished by using zip ties, cable ties, string, rope, or a clamp. Make sure the method of attachment isn’t too tight that it restricts nutrient flow to the branch. Once your larvae are sleeved, you can leave them there. The bag should be checked several times a week and moved when the food source is gone. When the larvae are final instar, immense care should be taken as larvae will chew a hole in the material if they run out of food. When they are prepupal, the larvae should be immediately removed from the bag and placed into something to pupate (next section). The last method used is slightly more complex, but gives great results. This requires the use of a large screen cage (or laundry bag) with a potted hostplant. Simply place the potted hostplant into a cage and add larvae. This method allows for ample airflow, and you will generally get larger larvae than you might on cut food. This method does require care with final instar larvae as they will drop off the plant and attempt to pupate in the potting soil. Plants should be switched out of the cage when they’re 90% defoliated. This allows the plant to rebound once it’s removed from the cage. Final instar larvae can be allowed to pupate in the potted plant, or can be moved to another suitable area.

Pupation

In this section, we discuss pupation needs. Most Sphingidae pupate underground (there are some exceptions), and so some sort of substrate is needed. The first method we discuss is the soil method. This method is the most “natural” as it allows the larvae to dig their own pupal cell. Prepupal larvae should be given 8-10” of soil, coco fiber, sphagnum, or other suitable substrates to dig in. The substrate should be lightly damp, not dry, and definitely not wet. This can be accomplished by a daily misting. The substrate can be kept in a bucket, or a container depending on how many larvae you are trying to pupate. Once the larvae bury themselves, wait about 8-10 days before looking for the pupae in the substrate. The easiest way is to remove handfuls of substrate until the pupae are recovered. If you are using soil for this, care should be taken so that accidental predator introduction is avoided. This can be accomplished by baking the soil in a 350F oven for 20-30 minutes, or pouring boiling water through the substrate. Wait until the substrate is fully cooled before adding larvae. The next method is the paper towel method. This method is often used due to its ability to keep larvae clean, free of predators, and easily observable. Prepupal larvae should be placed in a tupperware container that can be fully sealed (with minimal airflow). The container should have a paper towel placed down and misted with water until damp. Then place another, dry, paper towel on top. The larva can be placed on top of the dry paper towel. Fold the paper towel lightly (not creasing) over the larva until it’s all in the container. Close up the container and label with a date, this way you know when to check for successful pupation. The container can be lightly misted with water every 3-5 days in order to keep the humidity up. Larvae should not be overcrowded in a container. It’s best to place one larva per container unless the container is quite large. In a 5 gallon bucket, you can place many more larvae than in a quart container. If you are using a larger container or bucket, multiple layers of dry paper towel should be placed on top of the wet paper towel. This ensures the larvae have multiple layers and room to spread out. Resulting pupae can be removed after 10 days or when fully hardened.

Mating and Adult Care

Adult Sphingidae are easy to keep in captivity. Some species do not feed at all, while others do require food. Species that do not feed are easiest to get to mate in captivity as they just need a flight cage, darkness, and adequate airflow. Screen cages or zip-up laundry hampers make excellent cages for adult Sphingidae. For species that need to be fed, there are a few options. The first is the hardest, it requires live nectar plants. Pentas, Lantana, Moon Flower, Petunia, and Butterfly Bush are all good options for nectar plants. These plants can be placed in a large flight cage, adults will usually nectar at the plants around dusk and into the night. Replicating dusk conditions can be extremely hard, and often results in adults not feeding naturally. The next method is hand feeding. This is a cumbersome method, but is quite effective. First, start with a nectar solution, this can be a 50% honey-water solution, a 50% solution of sugar-water, or 100% gatorade/powerade. The nectar solution should be placed into a shallow dish, petri dish tops work extremely well, but bottle caps, or other similar items can be used. The adult sphingid must then be captured, and held with its wings closed between two fingers in one hand. You must then take the blunt end of a pin and unroll it’s proboscis into the nectar solution. This is best achieved by holding the adult close to the solution, with its legs touching the ground. Once the proboscis has been everted, place the end into the solution, at this point, the adult will usually try and move around, you can allow it to place one of the front legs into the nectar. Once the proboscis is in the solution, hold it there until you can see the adult drinking. This will look like the proboscis pulsing, usually up and down. After feeding is observed, you can let go of the adult. It will usually stay and feed for a few minutes. The next method is a combination of what was discussed so far. Create another nectar solution and place it into a dish or a cup (disposable plastic champagne glasses are perfect for this). Take a brightly colored plastic mesh scouring sponge and place it into the dish or glass. Fill the dish with the nectar solution and place it into a flight cage with the adult sphingids. At this point, you can either place the sphingids on the sponge to let them become interested, or leave it alone and they should find it on their own. Nectar solutions must be replaced daily or they will mold and create a poor food source. Once adults are adequately fed, they should mate. Once mating occurs, you can either add a potted hostplant for egg laying, or move the female into a paper bag for egg laying. The paper bag should only be used for Sphingidae that do not feed as adults. If a potted hostplant is not available, a branch of hostplant in a vase is equally acceptable.

BACK TO TOP

The first topic covered in this document is how to obtain Sphingidae to rear. This can be accomplished in a few ways. The easiest is to find an adult female and obtain eggs from it. This is discussed in detail in the last section, however it is worth mentioning here too. Adult Sphingidae can be placed into a styrofoam cooler, or into a paper bag to obtain eggs. While this works for many species (particularly ones that do not feed), some species do need a flight cage with hostplant to lay eggs. Specific methods of obtaining ovae from each species can be found on that species’ page. The next way to find Sphingidae to rear is by locating caterpillars. Searching plants at night, in mid-late summer is quite productive. Many species fluoresce with a UV flashlight, making it even easier to locate them. Once you have caterpillars, you can rear them using the methods below. This document is extremely general, specific information for each species and how to rear and breed them can be found on that specific species’ page. While not every species has this information yet, we are working on updating all of them. If you have questions, please contact us using the contact form, or email us at [email protected]. Have some additional rearing methods, notes, tips, or tricks? Shoot us an email! We will update this document and other areas on the site with new information, and we always credit those who supply us with it.

Rearing Sphingidae Larvae

In this section we discuss three methods of rearing Sphingidae larvae. The first method is rearing larvae in tupperware containers. This method is incredibly simple and involves placing the larva(e) and hostplant into a large enough container to rear them to pupation. Good containers should be sealed, but not totally airtight. If the container is completely sealed, adding a few ventilation holes to the lid or side is recommended. Cut hostplant material can be placed in the tupperware with the larva. The hostplant usually stays fairly fresh in the containers, though checking is required. Every day the containers should be vented, and excess moisture wiped down. Hostplant should be changed out daily, when the larva runs out of food, or when the plant is wilted or dry. For many species, it is imperative that frass is wiped out daily as it will mold and potentially kill the larva. When done properly, this is an extremely successful method. The next method discussed is sleeving. This method is much simpler, though attention is required for full-grown larvae. To sleeve larvae, simply obtain some light-weight mesh material that allows water to pass through, Tulle is a good option. BioQuip and other Entomological suppliers will often sell premade bags that can be used. Once you have obtained material, you should make a bag that is large enough to go over a branch (or several). It is important that the bag is totally sealed so that no larvae can escape. To sleeve a larva, simply place the larva in the bottom of the bag, and place the bag and larva over a branch of hostplant. The bag should then be carefully affixed to the branch in such a manner that no predators can get in, and the larva can’t escape. This can be accomplished by using zip ties, cable ties, string, rope, or a clamp. Make sure the method of attachment isn’t too tight that it restricts nutrient flow to the branch. Once your larvae are sleeved, you can leave them there. The bag should be checked several times a week and moved when the food source is gone. When the larvae are final instar, immense care should be taken as larvae will chew a hole in the material if they run out of food. When they are prepupal, the larvae should be immediately removed from the bag and placed into something to pupate (next section). The last method used is slightly more complex, but gives great results. This requires the use of a large screen cage (or laundry bag) with a potted hostplant. Simply place the potted hostplant into a cage and add larvae. This method allows for ample airflow, and you will generally get larger larvae than you might on cut food. This method does require care with final instar larvae as they will drop off the plant and attempt to pupate in the potting soil. Plants should be switched out of the cage when they’re 90% defoliated. This allows the plant to rebound once it’s removed from the cage. Final instar larvae can be allowed to pupate in the potted plant, or can be moved to another suitable area.

Pupation

In this section, we discuss pupation needs. Most Sphingidae pupate underground (there are some exceptions), and so some sort of substrate is needed. The first method we discuss is the soil method. This method is the most “natural” as it allows the larvae to dig their own pupal cell. Prepupal larvae should be given 8-10” of soil, coco fiber, sphagnum, or other suitable substrates to dig in. The substrate should be lightly damp, not dry, and definitely not wet. This can be accomplished by a daily misting. The substrate can be kept in a bucket, or a container depending on how many larvae you are trying to pupate. Once the larvae bury themselves, wait about 8-10 days before looking for the pupae in the substrate. The easiest way is to remove handfuls of substrate until the pupae are recovered. If you are using soil for this, care should be taken so that accidental predator introduction is avoided. This can be accomplished by baking the soil in a 350F oven for 20-30 minutes, or pouring boiling water through the substrate. Wait until the substrate is fully cooled before adding larvae. The next method is the paper towel method. This method is often used due to its ability to keep larvae clean, free of predators, and easily observable. Prepupal larvae should be placed in a tupperware container that can be fully sealed (with minimal airflow). The container should have a paper towel placed down and misted with water until damp. Then place another, dry, paper towel on top. The larva can be placed on top of the dry paper towel. Fold the paper towel lightly (not creasing) over the larva until it’s all in the container. Close up the container and label with a date, this way you know when to check for successful pupation. The container can be lightly misted with water every 3-5 days in order to keep the humidity up. Larvae should not be overcrowded in a container. It’s best to place one larva per container unless the container is quite large. In a 5 gallon bucket, you can place many more larvae than in a quart container. If you are using a larger container or bucket, multiple layers of dry paper towel should be placed on top of the wet paper towel. This ensures the larvae have multiple layers and room to spread out. Resulting pupae can be removed after 10 days or when fully hardened.

Mating and Adult Care

Adult Sphingidae are easy to keep in captivity. Some species do not feed at all, while others do require food. Species that do not feed are easiest to get to mate in captivity as they just need a flight cage, darkness, and adequate airflow. Screen cages or zip-up laundry hampers make excellent cages for adult Sphingidae. For species that need to be fed, there are a few options. The first is the hardest, it requires live nectar plants. Pentas, Lantana, Moon Flower, Petunia, and Butterfly Bush are all good options for nectar plants. These plants can be placed in a large flight cage, adults will usually nectar at the plants around dusk and into the night. Replicating dusk conditions can be extremely hard, and often results in adults not feeding naturally. The next method is hand feeding. This is a cumbersome method, but is quite effective. First, start with a nectar solution, this can be a 50% honey-water solution, a 50% solution of sugar-water, or 100% gatorade/powerade. The nectar solution should be placed into a shallow dish, petri dish tops work extremely well, but bottle caps, or other similar items can be used. The adult sphingid must then be captured, and held with its wings closed between two fingers in one hand. You must then take the blunt end of a pin and unroll it’s proboscis into the nectar solution. This is best achieved by holding the adult close to the solution, with its legs touching the ground. Once the proboscis has been everted, place the end into the solution, at this point, the adult will usually try and move around, you can allow it to place one of the front legs into the nectar. Once the proboscis is in the solution, hold it there until you can see the adult drinking. This will look like the proboscis pulsing, usually up and down. After feeding is observed, you can let go of the adult. It will usually stay and feed for a few minutes. The next method is a combination of what was discussed so far. Create another nectar solution and place it into a dish or a cup (disposable plastic champagne glasses are perfect for this). Take a brightly colored plastic mesh scouring sponge and place it into the dish or glass. Fill the dish with the nectar solution and place it into a flight cage with the adult sphingids. At this point, you can either place the sphingids on the sponge to let them become interested, or leave it alone and they should find it on their own. Nectar solutions must be replaced daily or they will mold and create a poor food source. Once adults are adequately fed, they should mate. Once mating occurs, you can either add a potted hostplant for egg laying, or move the female into a paper bag for egg laying. The paper bag should only be used for Sphingidae that do not feed as adults. If a potted hostplant is not available, a branch of hostplant in a vase is equally acceptable.

BACK TO TOP