|

Common Name(s): Elm Sphinx, Four Horned Sphinx

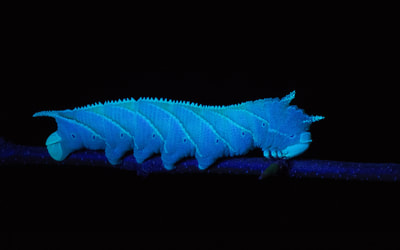

Ecology and Life History Overview: Adults are on the wing from May to October across its range, with most states experiencing one main flight from June to August. Adults of both sexes are attracted to light, and will show up throughout the night, with peak activity from approximately 2300-0200 hours (1). Females of this species tend to be slightly larger on average than males. Eggs are laid on hostplants and the young larvae camouflage very well on the undersides of leaves. When the larva is found on Elm, the roughness of the larva and the leaves really helps to hide the larva well. The large final instar is a vicious creature. While at rest, often along the midvein of the host’s leaf, they’ll tuck their head down, showing the horns. If disturbed, the larva will thrash about madly and click its mandibles. The larva can bite, and the bite is surprisingly painful. The green form and brown form larva seem to be found in equal amount when rearing and in the wild. The brown form blends quite well with dying elm leaves (1). Habitat and Searching for Larvae: Sam Jaffe notes he finds larvae on plants that are 15 to 40ft tall, but are growing beneath a larger canopy, so they are understory and surrounded by open air. He also notes that in Massachusetts, he happens to find the most larvae in September as final instars (11). In the Lehigh Valley area of Pennsylvania, larvae have been frequently recovered in Betula spp. growing along the sides of maintained paths near water. These larvae had preferences for the middle to upper branches of trees that are 30-40ft tall (1). I have found the association of water with this species to be fairly good. They can absolutely be found in other areas, but if you’re looking to start somewhere, check young Ulmus, Betula, or Tilia by streams (1). These larvae will glow when using a UV light for searching, making locating them quite easy (1). Rearing Notes: Females of this species lay readily in paper bags. The young larvae are quite easy to rear on Ulmus spp. Many young instar larvae can be reared together. It is important to separate the larvae as they get older as they will attack each other. We have found that placing large branches of cut Ulmus americana in a screen cage with multiple larvae does quite well, make sure the hostplant doesn’t touch the sides of the screen cage, or the larvae will bite through the mesh of the cage (1). You can sleeve this species on its hostplant, but we recommend not doing so in the final instar, as they will easily chew threw sleeves. Pupation can be achieved easily in soil, or in a container with several layers of damp paper towel on the bottom and more layers of dry paper towel on top. We recommend the paper towel method as disease and mold is much less likely as long as you are vigilant. Overwintering of pupae in captivity was found to be easiest in a refrigerator. Pupae are placed in a sealed tupperware container on top of some paper towels. 3-4 drops of water are added, then additional layers of paper towel to cover. Repeat layering like this for as many layers of pupae, only adding 3-4 drops of water per container (1). Adults will eclose the next year with minimal effort. Keeping them warm and humid will increase the development speed in the spring. The adults will mate fairly easily in a screen cage outdoors, or somewhere with airflow (1). Host plants: Click here to load this Caspio Cloud Database

Cloud Database by Caspio |

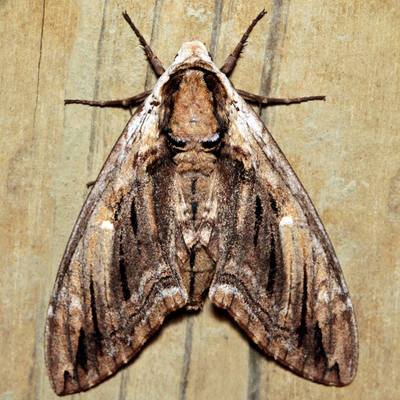

Adult description: This is another fairly large moth, with forewing lengths of 47-57mm (2). The base color is brown, with a brown-yellow upper and lower edge. Forewing costa and sides of thorax are whitish. The middle area of the wing is darker than the edges with a large white discal spot. The hindwings are primarily brown, with a cream band and dark black area along the edge of the wing. The body is brown with a black and cream zig zag band on either side.

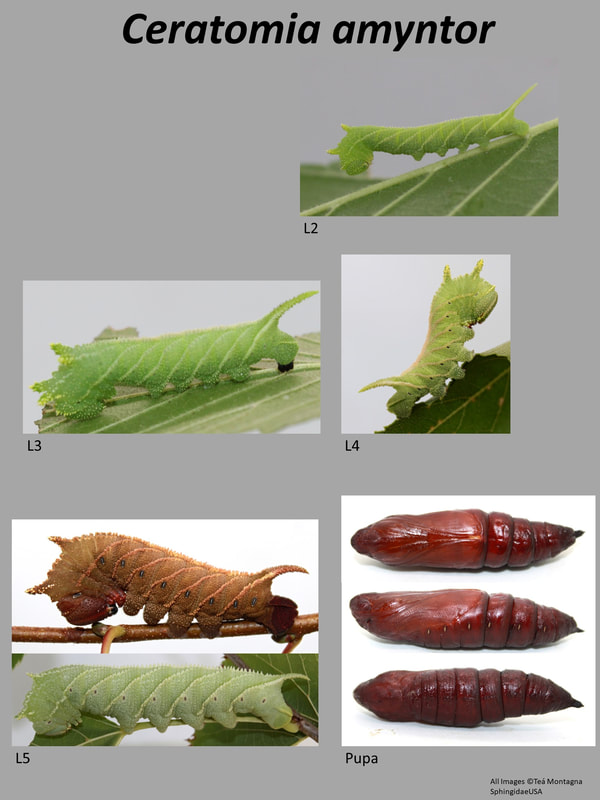

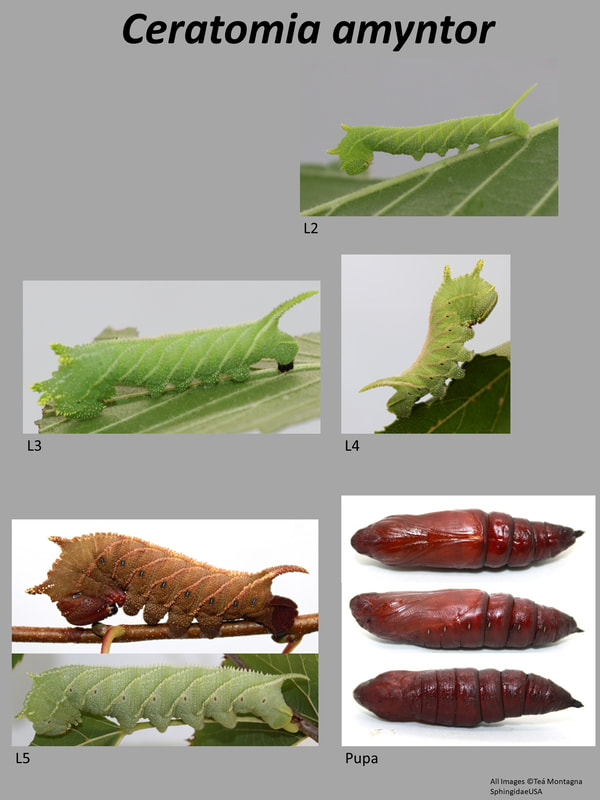

Larval description: L2: The small larva appears smooth. The horn is yellow and sticks straight backward. There is a prominent white dorsal stripe, and 7 white abdominal stripes. There are 4 small bumps on the thoracic segments. L3: At this stage, the larva is quite identifiable. The characteristic 4 horns are on the thoracic segments, and the larva is granulose. There are thin, cream abdominal streaks. The horn is yellow and relatively small, yet pronounced. L4: The larva is significantly larger and stockier in appearance. The thoracic horns are quite pronounced. The larva is covered in small granules that are most pronounced on the dorsal region and the horn. The horn is thicker and slightly slopes downward. The seven abdominal stripes are cream in color. L5: This large green or brown larva is quite granulose. As it’s common name implies, the distinguishing feature is this species has 4 horns on the top of it’s thoracic segments. The 7 abdominal stripes from the previous instar are still present. The granulose horn bends slightly downward, but can be reduced or absent, especially in captive rearing. The head capsule matches the ground color of the larva (green or brown), and has a pair of parallel stripes that match the abdominal stripes of the larva (cream or pink depending on the color morph). When the larva rests, it pulls it’s head in and down, showing off the horns, presumably to make it look more intimidating to potential predators. The horns are unique to this species, and coupled with how granulose the larva is, it is unmistakable. When handled, this larva will hiss and bite while thrashing around. They are capable of biting people, handle with caution. |

The gallery to the left contains photos of Ceratomia amyntor adults. If you have a photo that you would like to submit to us, please contact us.

The gallery to the right contains photos of Ceratomia amyntor larval and pupal stages. If you have a photo that you would like to submit to us, please contact us.

The gallery to the right contains photos of Ceratomia amyntor larval and pupal stages. If you have a photo that you would like to submit to us, please contact us.

|

|